Building with shells – historical references

The technique of making shell-based building lime is widespread across the globe in communities that don't have access to limestone bedrock. Often it’s island cultures on volcanic rock outcrops, or coastal communities with abundant shell material.

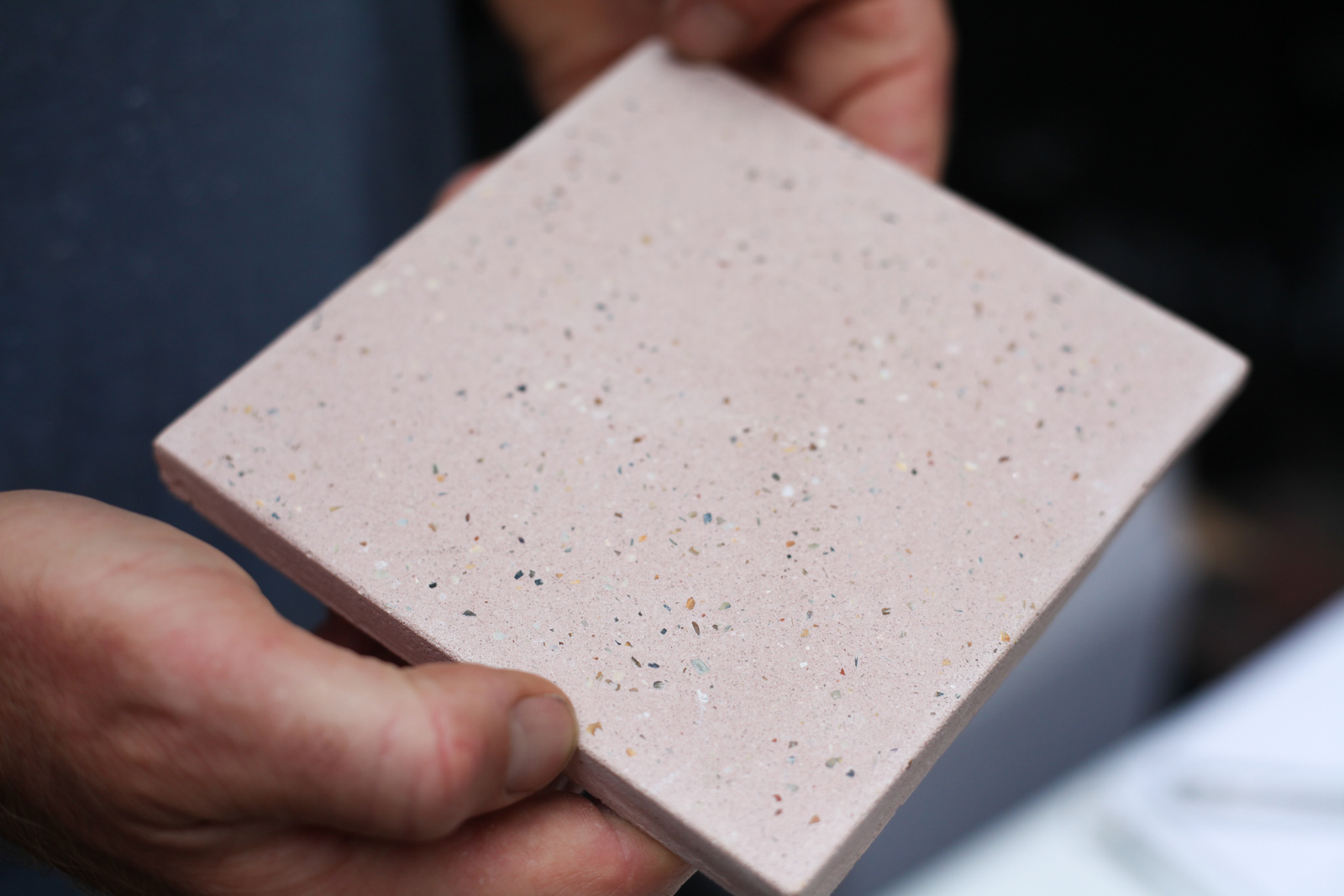

We have worked with lime-based building materials for the past 20 years, and have now used this knowledge to process waste shells from seafood restaurants and fisheries into building lime. See project: Building materials from shells

Lime is usually made by burning limestone rocks to create a dry white powder or wet putty that is used as a limewash paint, or mixed with aggregates to make a mortar for stone or brick masonry, plasters, renders and sometimes cast as solid walls.

It is different to modern cements in that it cures and hardens by absorbing carbon dioxide from the air, re-crystallising back to its original limestone chemistry. It is softer, more flexible and breathable compared to hard, brittle cements and crucially allows for masonry units such as bricks and stone to be easily cleaned and reused. It is made from one source ingredient, whilst cements are a blend of limestone with other, often harmful and toxic substances. Cements are also burnt at much higher temperatures in the kiln, emitting huge amounts of CO2 in their production.

If the cement industry were a country, it would be the third largest emitter in the world (8% of total CO2 emissions) - behind China and the US. Cement production contributes more CO2 than aviation fuel (2.5%) and is not far behind the global agriculture business (12%).

Chatham House - 2018

Lime has been made and used for 1000s of years in all climates around the world, and only fell out of favour in the 1950s as cements became the go-to material for increased speed of construction and amazing strength. Shells from oysters, mussels, scallops, whelks, crabs and lobsters can all be processed into building lime.

There are some excellent historic references to the use of oysters in lime production. This is a great quote about the architect, diarist, and the first curator of The Royal Society: Robert Hooke – 22nd April 1696

“Doctor Hooke sayd that as to Lime he had reason to believe that no substance whatever make so durable plaster as oyster shells and that instead of sand he thought nothing better than ground cinders which two would together make a much harder and more durable mortar than any other whatever”

Extract from a PhD thesis on Sir Christopher Wren and the Royal Society by James Campbell – University of Cambridge.

Oysters have been linked with humans at every point of our history, due to the shells longevity, they exist as our historic detritus. The shells are used for DNA analysis and dating of human settlements across the world. The oyster was an easily available source of protein found in sheltered estuaries all around the UK.

The native oyster to the UK is a bivalve with 2 flat shells (Ostrea edulis), and is only in season for harvesting between September – April. To bridge the gap during the summer, the Pacific Oyster (Crassostrea gigas) was introduced here from Japan.

In the USA an oyster based lime mortar for buildings was produced in the South Eastern coastal states and named ‘Tabby’. The mortar was produced in large quantities and consolidated into timber shuttering, like rammed earth, to produce solid thick walls and buildings. It is dated from the late 1500’s to the 1850’s, and could have come from Spanish settlers and/or Arabic or African roots. In Arabic tabbi means a mixture of mortar and lime, and in Spanish tapia means a mud wall. The material was a mixture of calcined (burnt) oyster shell (the lime binder), ash (from the burning process) and sand. The ash from the burning of the shells added strength to the final mortar. Several experiments re-enacting the process of the oyster shell burning have successfully been undertaken in various parts of America in order to repair buildings or replicate historic techniques. One project in Virginia constructed a traditional oyster burning technique called an Oyster Rick, a large wood fuelled bonfire that fires the shells to turn them into quicklime (Calcium Oxide).

In the Spring of 2017 Local Works Studio visited the Faroe Islands in the North Atlantic to see their shell lime mortar on this limestone-free volcanic island group. The Faroes were settled by Irish monks and then Viking-aged settlers in the 9th century. They found a barren group of islands with little raw materials beyond its hard, black basalt rock. There are stories of whole timber buildings being sailed over from Norway to be re-built in order to have some meaningful shelter, and to maintain a link to their past.

The early masonry buildings are survived by the impressive cathedral ruin of St Magnus in the village of Kirkjubøur on the island of Streymoy. The building was started in 1300, and still stands today, roofless but semi-protected for on-going repair work since 1997. The hard basalt stones are mortared with a shell lime material made from shell sand that makes up some of the local beaches. The shell sand was burnt for quicklime and added to the beach deposit (aggregate) to make the bedding mortar for the large stones. The shell sand was also used in its raw state as internal flooring of the early houses.

In the UK there is historic evidence of shell lime mortars in Scotland, where the geology proved challenging in some areas to use a lime rock for production:

‘Scottish lime, particularly in the Western Isles, was also produced from sea shell. When burnt in a kiln, the shells are reduced to lime. The loose nature of the material allows it to burn easily and completely, so that the lime produced is not contaminated with lumps of un-burnt lime. This produced a very high quality and pure (or feebly hydraulic) lime that was particularly good for internal plaster work’

Clare Torney – Lime Mortars in Traditional Buildings – Historic Scotland

It is possible to use oyster shells as a source material for lime production. They can make a beautiful mortar that is very pure and easy to work with. These findings correspond with historic text that oyster lime is a very fine material, possibly saved just for the best work such as internal plastering and decorative applications.

Local Works Studio are always looking to develop new and forgotten materials, using local waste and by-products. We feel there is much more potential for vernacular crafts to contribute to current and future practice and materials, especially concerning the use of waste and sustainable principles.